Broadway is one of New York’s biggest attractions with numerous different shows being on every day. I knew I wanted to see Hamilton but I also knew that I wanted to go for some lesser known Off- or even Off-Off-Broadway show as.

(Trivia: A Broadway show is not necessarily a show on Broadway. Instead, to classify as such it simply has to be staged in a Manhattan theatre with more than 500 seats. Theatres with 99 to 499 seats are Off-Broadway. The really small ones are Off-Off-Broadway.)

How to get cheap Broadway tickets

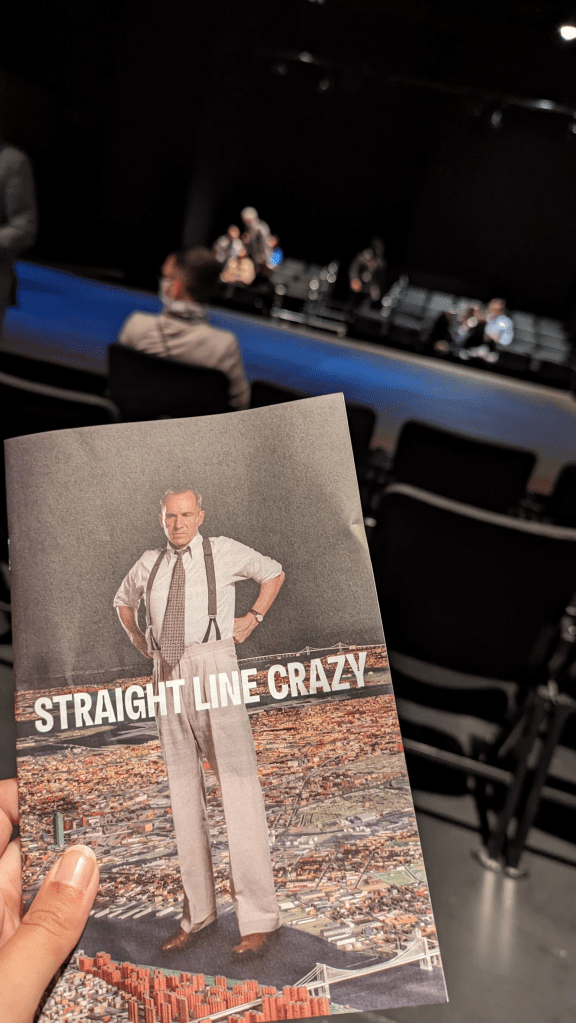

Should you ever want to see a Broadway show, make sure not to buy the ticket directly from the theatre. One well-known way of getting cheap tickets is to go to the TKTS booth on Times Square, where they sell discounted tickets for shows on the same or on the next day. A maybe even better alternative is the app TodayTix. I have had it for a few months, just to get a feeling for prices and offers and that really helped. So when I saw a discounted ticket for Hamilton for only $100 (normally seats are $200 and more), I jumped at the chance. I also used the app to check out which lesser known shows are on and „Straight Line Crazy“ came up.

„Straight Line Crazy“ premiered in London’s West End and was taken to Broadway mid October. The play was written by David Hare and fictionalizes two pivotal moments in the life of Robert Moses, New York City’s famous urban planner. Since the play is only on for two months and Ralph Fiennes (aka Lord Voldemort) in the lead role adds some stardom and glamour to it, tickets were highly coveted and most shows were already sold out. If there were remaining seats, then only for around $230. However, in TodayTix you have the chance to get so-called Rush tickets for $29: Those tickets are severly limited and become available at 9am for same-day performances. I tried two days in a row and the tickets were instantly sold out. On the third day, I had basically given up and only tried for fun but luck was on my side. I got a ticket!

So, who is this Robert Moses?

Robert Moses – aka the Power Broker – was an urban planner who shaped the face of New York in the mid 20th century. Although he was never elected into any office, he is said to have held exceptional power and influence. Apart from numerous urban parks, he also built 11 public pools, 255 playgrounds and 17 miles of beaches.

While pools, playgrounds and beaches might sound amazing, Moses‘ work and legacy are extremely controversial. For instance, he believed strongly that the future belonged to the car and not to public transport, thus buidling more and more roads but no train tracks or subways. When New York started to suffer from traffic congestion, Moses‘ approach was simply to build even more roads. More prominent criticism against Moses focuses on issues of race and class. He is said to have built bridges particularly low so that buses could not access the nicest beaches and parks, thereby ensuring those beaches and parks belonged to the car-owning middle classes only. It is only fair to mention, however, that this point is fairly contested. Yes, the bridges were too low for buses but back then parkways in general barred commercial traffic, and parks and beaches could have been accessed by public transport via other roads (information found in the City of New York Museum). Moses also built the Bronx Expressway (built between 1948 and 1972), the first US highway built through a crowded urban neighbourhood. As an effect, about 40,000 people lost their home and the character of the Bronx was severely affected as the expressway lowered property value in the area, keeping large parts of the Bronx in poverty. Some say that there would have been less destructive possibilities for an expressway but that Moses chose this route on purpose to maintain class segregation. Intentionally or not, Moses‘ work definitely benefitted the white middle classes.

Enter the antihero

„Straight Line Crazy“ focuses heavily on all the controversies and criticsm that still surround the character of Robert Moses. Fiennes brings a classic antihero to stage that doesn‘t allow for any sense of sympathy or empathy. Moses is portrayed as a power hungry master builder, who cares very little for the feelings of everyone around him and even less about the wants and needs of the people. „Those who can, build. Those who can’t, critize“, Moses famously says. His aim is to leave his mark in New York and to shape a model city that can act as a blueprint for urban planners all over the world. Strokes of fate – such as his (absent) wife succumbing to alcoholism or his most cherished co-worker quitting – are acknowledged but simply dealt with by going back to work and designing more streets and more expressways.

While the first act shows a pivotal (fictional) moment that would eventually lead to his rise in power (convincing NY governor Al Smith to get behind him on his plans for a Long Island highway system), the second act focuses on his influence crumbling. We are now in the mid 50s and Moses has to face a new kind of oppontent. It’s no longer bribe loving politicians or wealthy aristocrats but „the minstrels and artistic women with handbags“. Enter Jane Jacobs.

Jane Jacobs was a writer, a philanthropist and an activist. Although her and Moses would never meet (neither in real life nor in the play) she is known as the woman who ultimately brought him down. The play’s second act is all about Moses‘ plan to extent Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park. If you’ve ever been to New York then you might know that it’s fairly easy to get from North to South and vice versa. Going from West to East, however, is a whole different story. The city is just not made for horizontal traffic and roads are blocked constantly. So building an expressway through Washington Square Park and thereby no longer forcing people to bypass it, does make sense – from a car driver point of view. Jacobs and other fellow activists fiercely dissented. They claimed that the park was for the people and that an expressway would destroy the West Village community.

The City of New York Museum found good words to describe Moses‘ and Jacobs‘ conflicting ideas: „Master Builder Robert Moses took a bird’s eye view of the city, seeing it as an organism requiring arteries and connective tissue. By contrast, Jacobs saw the city from the ground up, as a place of streets and people, a spontaneous „ballet“ to be lived at eye-level.“ Those stances were also played upon on stage, with Jacobs being seen at public protests and with Moses being seen in his office symbolically standing and moving on an oversized map of New York City.

In the end, Jacobs and her fellows won the Washington Square Park controversy and Moses had to realize that things changed: people would no longer simply be ok with what politicians and urban planners did but took to the streets to voice their opinions. Times had indeed changed.

Or have they?

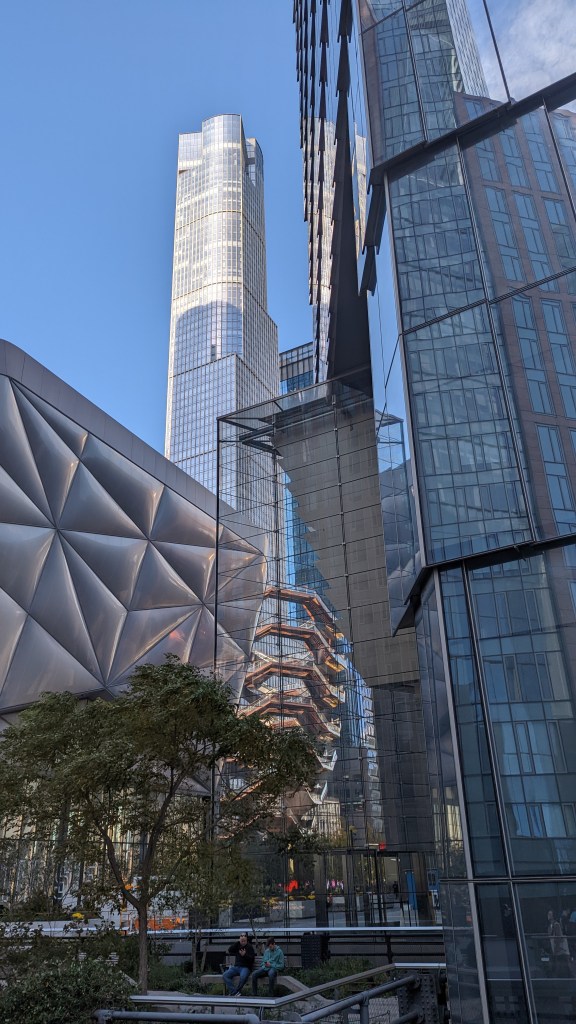

I call myself very lucky to have seen „Straight Line Crazy“ in New York, surrounded by a New York audience. It’s very intriguing to learn about the shaping of New York City and to be spit out onto the streets of said city after the curtain call. Interestingly enough, the play was staged at The Shed theatre in the Hudson Yards area – an irony that eluded nobody in the theatre.

Priced at $25 billion, Hudson Yards is the most expensive real-estate development in US history. The project was advertised as „a neighbourhood for a new generation“ and as „the new heart of New York“. Over the past few years, the area has undergone major redevelopment with plans for a total of 19 new skyscrapers. The new neighbourhood is supposed to extend midtown Manhattan business to the island’s West.

It is pretty clear that a project of this scale would face vehement criticism: In short, Hudson Yards is said to have no character whatsoever and to contribute to the „Disneyfication“ of Manhattan. In Curbed Magazine, Justin Davidson calls Hudson Yards „a corporate simulacrum of a city“ (full article) and Ryan Sutton from The Eater calls it „a reinvention of New York that would make a Las Vegas casino-owner proud“. He critizices that the developers‘ decision to grant leases only to established businesses and restaurateurs was „about rich men helping other rich men stay rich“. (full article – highly recommend it!) I can’t shake the feeling that Robert Moses would have approved.

My apartment is actually very close to Hudson Yards and while it looks pretty from the outside and I appreciate the view every morning, it still kind of feels like a ghost town. Most office spaces are not yet rented out and the only reason to go there just now is either for touristic activities such as visiting the Edge Observation Deck (where a can of beer is $13) or to go shopping (for luxury goods or overprized groceries from Whole Foods only).

This crass elitism becomes even more obvious in contrast to surrounding areas. You only have to walk up a few blocks and you’re in Hell’s Kitchen, where you have tons of small local restaurants and little bodages and where, up until a few years ago, rents were kind of affordable. According to Zumper, the average rent for a one bedroom in Manhattan is currently $4,075. (For comparison: the median household income in Manhattan is $117,926.) In Hell’s Kitchen the average rent for a one bedroom is now $4,250 – a steeper rise than in most other areas. I can’t help but wonder whether this is a direct effect of the Hudson Yards redevelopment.

When I meet New Yorkers here, I always ask them about the balance between quality of living and cost of living in the city. The other night I met a middle aged guy, who is sharing an apartment with his daughter in Hell’s Kitchen, and who explained: „I love the city. My daughter loves the city. We will never move. But I have given up hope on being able to leave her any money when I die. We sat down together, we discussed it and we are both willing to make that sacrifice for a life in New York.“